You may have noticed an uncompleted form in your estate planning documents. It is usually titled “personal property list” (or something similar). It’s actually important for you to consider. Let us be clear: we are a Tucson elder law attorney firm, and we don’t know the law in other states. What we say about Arizona law might or might not apply to you if you don’t live in Arizona. Talk to your own lawyer. If you live in Arizona, though, you have the opportunity to include reference to a personal property list in your will. You might see a paragraph that starts with something like “I may make a list of personal property and who it is to be given to….” That’s an invitation to you to address an important issue.

If your will refers to it, and you have completed a personal property list, it acts as if it was part of your will. It identifies individual items and who should receive them after your death. The best part: you can change it from time to time, without having to rewrite your will. You can work on it over months or years, refining it after conversations with your family and friends. You can’t put cash, or real estate, or stocks and bonds, on the list. Saying “$10,000 to my favorite massage therapist” might be a fine idea — but not on the personal property list. Where the personal property list really shines is with family heirlooms, items with sentimental value and things your family members really, really want to receive. Use the personal property list for your grandmother’s cedar chest, or the original letter signed by President Grover Cleveland. You can also use it for the painting hanging in your living room. It works well for silverware, family china, individual items of jewelry (make sure you can describe them adequately).

No. Your will and estate plan will still be fine, even if you never complete the personal property list. Your family, though, will be much happier if you do fill it out, and keep it updated. At a recent meeting of the American College of Trust and Estate Counsel, we listened to an excellent presentation from one of its Fellows, John A. Warnick, from the Purposeful Planning Institute in Denver. Mr. Warnick collected admittedly anecdotal evidence of family conflicts over personal property, and urged people (and lawyers) to pay more attention to the distribution of tangible items after a death. Clients too often tell us: “I’m just going to leave all the personal items to the kids. They’ll have to fight it out.” Others say: “let’s leave everything to Diane. She can decide who gets what.” Remember that, by definition, you won’t be around to mediate disputes among your children (or other family members). Lawyers all too often see families quarrel over items that have more sentimental than economic value. You can help prevent that by giving your children directions. You might well think this doesn’t apply to you. Your family, unlike so many others, gets along pretty well. They’ve long been able to work out their differences — under your watchful eye. They should be able to figure out how to divide your household effects, right? Unfortunately, you will never know.

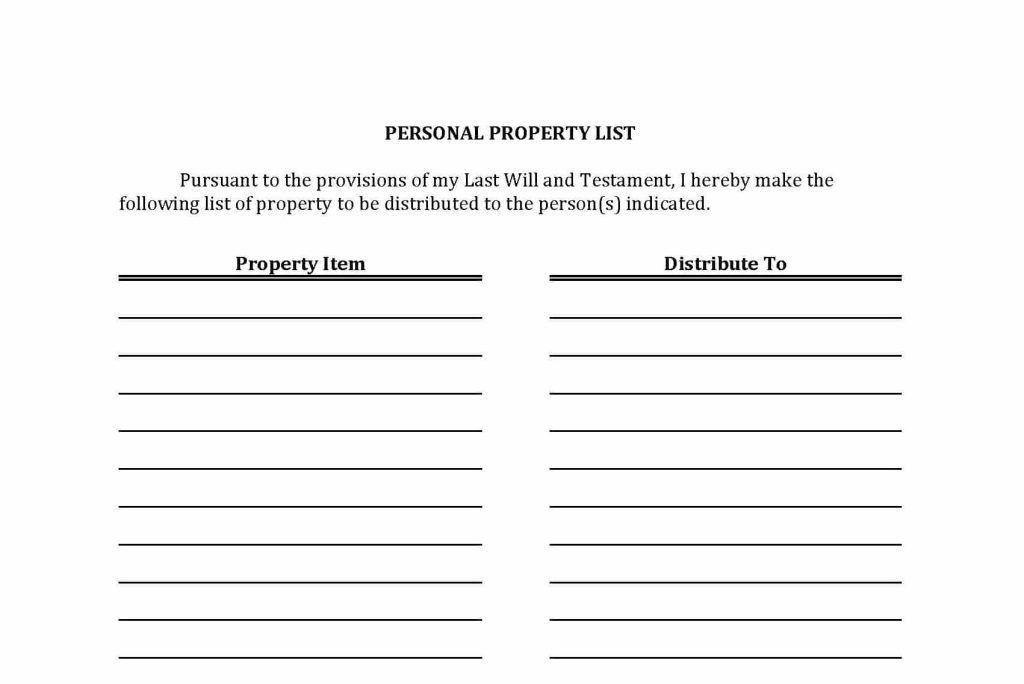

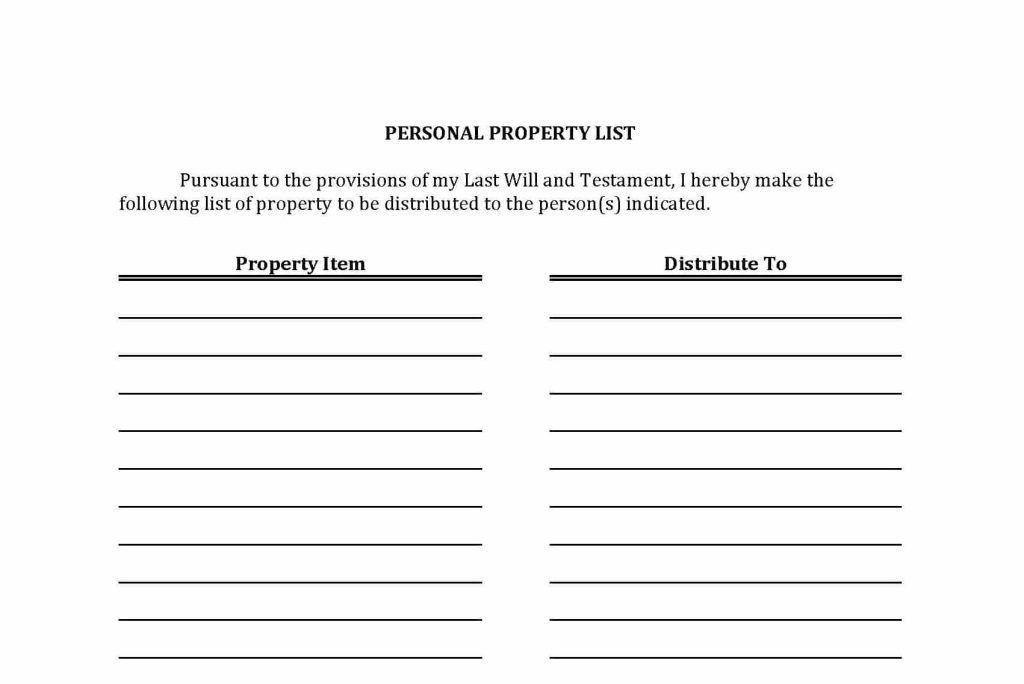

If you completed your estate planning with Fleming & Curti, PLC, you already have a simple form. It has one column for a description of the items and another for the recipient. You can make innumerable copies of that form. It’s also perfectly fine to hand-draw a list on a legal pad, too. You can update the list any time you want. Cross out items you give to the recipient during life. Add new items as they occur to you — or someone expresses a strong interest in them (or a lack of interest). Delete people who are no longer as important to you. Never think of the list as “done.” But (and this is important) do sign the list. Just to make things clear, include the date(s) as you update it. You don’t need to send your lawyer a copy of your list (though it doesn’t hurt anything if you do). Keep the original list with your original will. If you have created a trust, your list should probably be mentioned in the trust document, too. Talk to your lawyer if you have any questions about the list, what should be on it and what it should look like.

It wouldn’t hurt if you could create a video log of household items, with your voice. That might help dispel concerns that “stuff” might have disappeared shortly before, or after, your death. But that’s a topic for another day.